Name a trending story of the day and one is likely to find a whistleblower lurking just below the surface. Think about it: the latest Hunter Biden news came from a whistleblower, multiple FBI whistleblowers are wreaking havoc at the J. Edgar Hoover Building, and Elon Musk is accused of trying to bury a potential SEC investigation into his purchase of Twitter brought forth by – you guessed it – a whistleblower. These informants who expose possible wrongdoing are growing in number and influence – but why now?

Whistleblower Mania

This month, Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH), the ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, claimed that there were more than “14 FBI agents who have raised concerns … over matters including the controversy surrounding a school boards memo, Jan. 6, and pressure to label cases domestic violence extremism,” according to the Washington Examiner.

This month, Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH), the ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, claimed that there were more than “14 FBI agents who have raised concerns … over matters including the controversy surrounding a school boards memo, Jan. 6, and pressure to label cases domestic violence extremism,” according to the Washington Examiner.

Over at the U.S. Senate, Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) wrote a surly letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland about what he saw as the AG’s attempt to stop Department of Justice officials from talking to members of both legislative chambers. Grassley and others maintain a Garland missive was aimed at silencing and perhaps even intimidating whistleblowers. The senator came to the defense of agency informants with this memo:

“I write this letter to make clear to you that whistleblowers are the most patriotic people I know and they play an integral part in ensuring that inappropriate influences, political influence, and improper conduct within the Department and its components, such as the FBI, are exposed.”

Then the 88-year-old-Iowa senator hammered down:

“Accordingly, it is often only because of whistleblowers that Congress and the American people are apprised of the type of wrongdoing that your memo seeks to protect against. For example, it is only because of whistleblowers that I have been made aware of wrongdoing, including political bias infecting investigative matters, by ASAC Thibault and others during the course of the Trump and Hunter Biden investigations that I’ve recently written to you about.”

Attorney General Merrick Garland (Photo by Evelyn Hockstein-Pool/Getty Images)

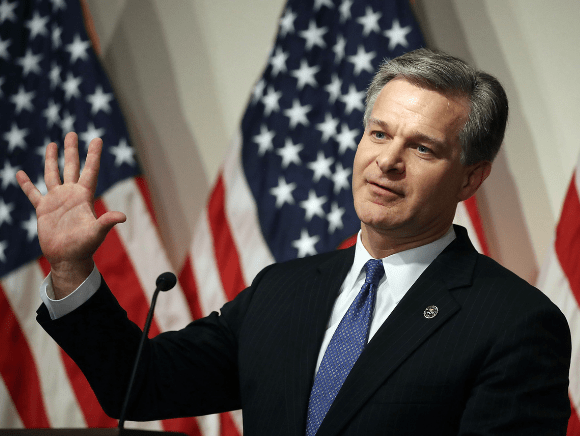

So contentious is the situation that those informing on the agencies in which they work have had to seek legal representation. An attorney acting on behalf of FBI whistleblowers contends the agency’s Director Christopher Wray “did not take action when confronted with issues inside the bureau that ranged from agents being forced to sign false affidavits to sexual harassment claims,” according to the New York Post. Kurt Siuzdak also told the Washington Times, “I’m hearing from [FBI personnel] that they feel like the director has lost control of the bureau.” Siuzdak, a former FBI agent who left his post after a quarter of a century, told the Times he called it quits “because of alleged politicization at the top and said FBI leaders aren’t being held accountable.”

Meanwhile, Attorney General Merrick Garland has vociferously denied the whistleblowers’ claims, however he certainly must know there are restraints in place when dealing with whistleblowers within his own agency. The Department of Justice Office of Recruitment & Management (OARM) is tasked with protecting these individuals from reprisal. From the DOJ website: “The Director of OARM is responsible for ensuring that former or current employees of, or applicants for employment with, the FBI are protected from reprisal for reporting allegations of wrongdoing, and to order appropriate corrective relief in cases in which OARM determines that an unlawful reprisal for whistleblowing has occurred.” In other words, whistleblowers have rights, too.

Qui Tam is Nothing New

Qui Tam is the abbreviated Latin phrase used as far back as the 7th century for the concept of blowing the whistle on corruption. Whistleblowers International advocates for these people and offers a history of the longtime practice. It points out that US whistleblowing goes back to the Founders’ days. In 1773, Benjamin Franklin “exposed confidential letters showing that the royally appointed governor of Massachusetts had intentionally misled Parliament to promote a military buildup in the Colonies,” according to Whistleblowers International. They go on to say, “Since its foundation, America has fostered and embraced a culture of civic responsibility in order to protect and benefit the public good.”

However, there has been an ebb and flow to the practice throughout American history. That changed in 1986 when Congress amended the False Claims Act. The alterations provided more robust protections for those who wished to come forward and blow the whistle on an organization. As well, the penalties for those making false claims were increased.

However, there has been an ebb and flow to the practice throughout American history. That changed in 1986 when Congress amended the False Claims Act. The alterations provided more robust protections for those who wished to come forward and blow the whistle on an organization. As well, the penalties for those making false claims were increased.

Still, whistleblowing is an act of courage, fraught with landmines, personally and professionally. But perhaps that is the point – those willing to take such a risk with nothing to gain promotes believability. Thus, it is difficult to dismiss their anonymous information. Meanwhile, the whistle keeps blowing louder and more often these days, perhaps for a good reason. That such an act has become a virtual necessity is trouble in and of itself. As Jordan told the Washington Examiner, “I’ve never seen anything like this. It seems like every other week, we’re hearing from someone.”