In September 1989, I toured East Germany, researching a Cold War thriller I had sold on the basis of a synopsis and sample chapter. The political background of the story was the reunification of Germany at a conference to be held in the East Berlin suburb of Potsdam, 50 years after the Potsdam Conference – famously attended by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and US President Harry Truman – that would decide the terms for the end of World War II. First on the table was dividing aggressor nation Germany and its capital into western and eastern sectors. My working title was Potsdam 1995. All that remained was to scout out locales and do the writing.

But geopolitical forces were in play and tectonic events in the offing, far more fateful than my little fictional project. In the two years since President Ronald Reagan’s “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” speech at Berlin’s iconic Brandenburg Gate, the Soviet Union had been in perpetual crisis mode, grappling with economic stagnation and growing political unrest among the Warsaw Pact nations from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Gorbachev’s much ballyhooed policies of “openness” and “restructuring” (glasnost and perestroika) were, as would soon be obvious, only rear-guard actions meant to stave off outright rebellion and systemic collapse.

I was aware of these ominous rumblings, to be sure, as was my publisher, but we both thought the 70-year Soviet empire would last another decade, or at least long enough to complete the book and turn it over to the marketing and sales departments. How wrong we were!

On Nov. 9, 1989, just a month and a week after I got home from my research trip and set to work on the opening chapters, the Berlin Wall came down amid great clouds of concrete dust and riotous demolition parties. It was a glorious day for the Free World and the Iron-Curtained millions who had longed to be free — but a calamitous one for me. In the heady times that followed, the satellite nations of the USSR threw off their chains. I desperately reassured my publisher that, with some strategic plot-tinkering, my project was still viable.

The final manuscript, rechristened Duel of Assassins, was duly finished and accepted and the project published. But when it came time to propose my next book, I was sternly cautioned to steer clear of a thriller entirely. The genre was dead, I was told flatly, which I understood to include political and spy. Its demise was collateral damage of the outbreak of global peace.

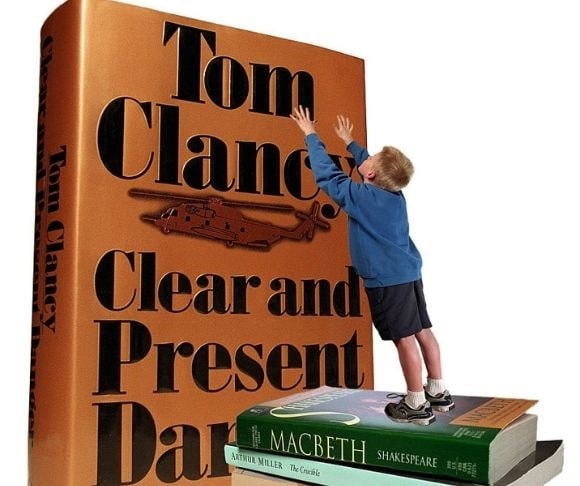

A bit hasty, that prediction, it turned out. Tom Clancy, churning out his doorstop blockbusters at that time, never missed a beat. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the ex-insurance salesman deftly about-faced his serial hero, Jack Ryan, in order to hurl him against Colombian drug lords in Clear and Present Danger. In so doing, Clancy was taking a page from Ian Fleming. Decades earlier, the politically astute British spy novelist had replaced James Bond’s nemesis, SMERSH, a real-world Soviet spy agency, with SPECTRE, a wholly fictitious crime syndicate with worldwide tentacles.

Death of the Thriller Has Been Greatly Exaggerated

In any case, thrillers have not died — and will not. They are as ancient as the Iliad and as topical as the crisis du jour. The more godawful the news, the more we clamor to experience vicarious danger. No matter how brutal the endless banner headlines, we can always find cozy, safe spaces in the next suspenseful chapter of a well-crafted book or installment of a streaming series, be it ever so bloody.

Safe, because the genre calls for a suicidally brave and well-equipped hero to face the slings and arrows and guarantees us an acceptable resolution at the end of the entertaining ordeal. Beats reality any day.

Even US presidents, drained by the daily demands of crises and cataclysms, have been known to take refuge in the latest page-turner. John F. Kennedy loved to read history, especially Churchill’s massive works. But the fiction he liked best featured the intrepid, womanizing exploits of James Bond. (From Russia With Love was said to be his favorite.) And Reagan famously helped launch Tom Clancy into stratospheric best-sellerdom after pronouncing The Hunt for Red October “a perfect yarn.”

(Photo by Al Seib/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Ghost-written projects aside, the current crop of thriller writers has much to recommend it. Vince Flynn remains a favorite though he died a decade ago. His fearsome, square-jawed assassin, Mitch Rapp, was launched just in time to join the great war on terror. And he was far from alone.

With Al Qaeda, ISIS, and their offshoots plotting villainy on soft Western targets, it wasn’t long before the ranks of thriller writers were swelled by a new cadre of specialists — ex-Delta operators, SEAL Team Sixers, Green Berets, and Recon Marines — guys who’d served in the Sandbox and lived to tell about it in gritty and convincing techno-detail. A few of these, like Jack Carr, author of the popular James Reece thrillers, also brought a keen story sense and descriptive eye. Others, predictably, fall short, though their prose is impressively larded with military acronyms, barracks jargon, and the latest in operational paraphernalia.

Flynn also was one of the few who understood that his hero needed to confront insidious cabals not only in exotic foreign capitals but also in the power centers of DC — in congressional caucuses, lobbyist lunches, and Georgetown drawing rooms. Rapp, I’m happy to report, soldiers bravely on in the capable hands of thriller writer Kyle Mills, as does Clancy’s Jack Ryan under various bylines.

As a final note, Clancy, creator of the techno-thriller and master of technical verisimilitude, enjoyed occasionally taking liberties with facts and indulging his fancy. An example occurred in the previously mentioned Clear and Present Danger. The author wanted a bomb to explode silently on the mountaintop hideout of a Colombian drug baron. When the latest in weaponry wasn’t up to Clancy’s specifications, he simply invented his own hardware. He called it the “Hushaboom.”

“I got the idea from The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show,” Clancy told an interviewer.*

*Philip Morris Magazine, summer 1991

~Dan Pollock is still writing thrillers. His newest project takes place in the first century, free of the unpredictability of current events.