The US is whistling past the graveyard when it comes to achieving and maintaining an adequate defense industrial base (DIB) and supply chain. Keeping America’s warships, tanks, and aircraft supplied to meet real-time national security threats adequately is a challenge under the best of peacetime circumstances. With the depletion of US war-readiness stocks to support Ukraine’s critical struggle against the unprovoked invasion by Russia and now resupplying Israel in its war on the murderous Hamas terrorists, replenishing US artillery and precision-guided munitions inventories must rely on an uncertain defense industrial base and associated supply chain.

For a while, America’s national security apparatus has known a shortage of computer chips. US domestic semiconductor production was once plentiful – but production was outsourced overseas for cheaper fabrication, mainly in Asia, and is now just beginning to return to homeland companies.

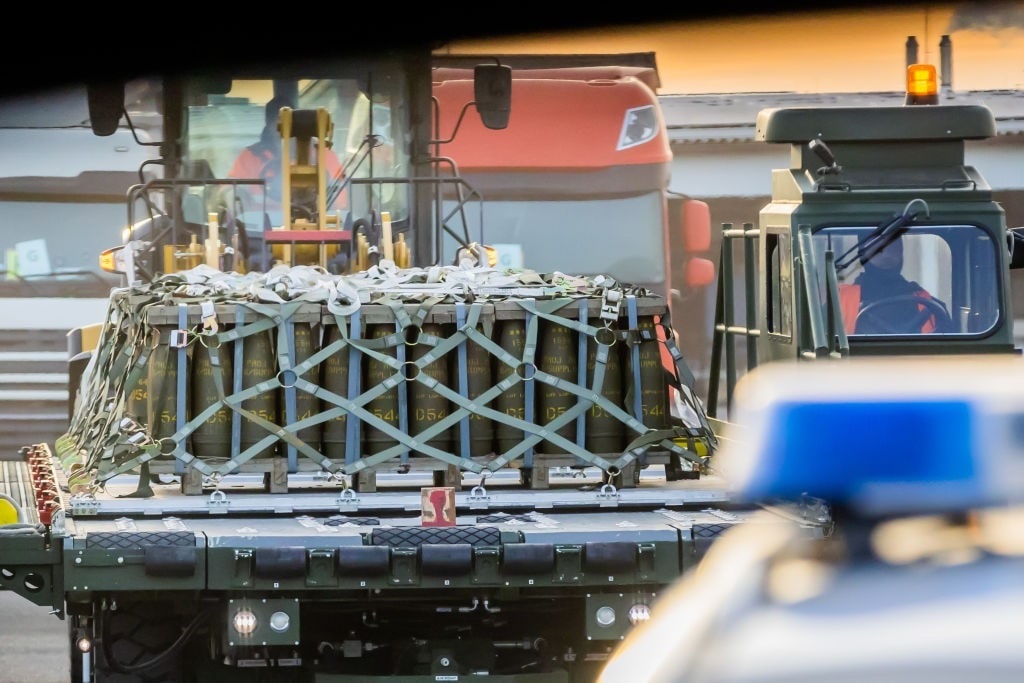

A Waning Supply Chain

(Photo by Christoph Soeder/picture alliance via Getty Images)

That supply chain feeds the national defense industrial base. Many are realizing that the US defense industrial base, even if it had a robust supply chain, might be incapable of turning out weapons and munitions at a scale to meet all the global threats the US faces. Several factors are in play. First, most aerospace and defense contractors have the capacity to handle the current contracts and no more. There is no US Defense Department funding for excess capacity in producing armaments, just in case. Varying with annual funding budgets, defense production will expand or contract within a narrow range. Second, the Biden administration is depleting current inventories of munitions and weapons to support Ukraine and Israel.

Third, mergers and consolidations of corporations have reduced the number of suppliers of critical warfighting materials. “There are only two contractors today that build large numbers of rocket motors for missile systems used by the Air Force, the Navy, the Army and the Marines, down from six in 1995,” Eric Lipton said, writing for The New York Times. Last, for the Department of Defense to address ways to grow the DIB, it must be able to adequately assess the US defense industry’s capacity to understand where to put effort. Currently, the only such assessment was a 2022 report, “State of Competition within the Defense Industrial Base,” that failed to shed much light on the problem.

The director of national intelligence echoed this idea in his fact sheet “A Spotlight on Defense,” written for the National Supply Chain Integrity Month edition. A critical counterintelligence risk is the “Inability to identify sub-tier suppliers subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a foreign government…Difficulty identifying threats, vulnerabilities, and risk in sub-tier supply chains enables the insertion of counterfeit or compromised components into the DIB supply chains.”

Urgency to Fix Defense Industrial Base Apparent

A recent report from The Wall Street Journal explained the urgency of the need to fix the DIB capability to scale up to meet a growing critical near-term wartime demand. A supplier of missile-defense systems produced in Kongsberg, Norway, is a principal supplier of a highly sought-after system that can launch up to 72 missiles to destroy drones, helicopters, and various other incoming threats. “(T)he National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System, or Nasams, is what protects the airspace over the White House. When first deployed in Ukraine in 2022, it recorded a 100% success rate shooting down cruise missiles and drones in its first few months,” the WSJ said. Consequently, orders for the air defense system are creating a backlog that will take years to fill. The Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace factory officials say it takes two years to produce one complete system. Unfortunately, the exigencies of war are an impatient mistress.

Reports from the battlefield in Ukraine show that during the summer counteroffensive, Kyiv’s forces were firing up to 6,000 rounds of artillery shells daily. Imagine the demand for artillery munitions if the US were engaged against China in stopping an invasion of Taiwan. In the Indo-Pacific, US naval gunfire would be the artillery, and the need for heavy fire support could outstrip US Navy inventories in a matter of a few weeks. The objective must be to get an industrial base capable of rapidly scaling up to meet any extraordinary requirement. Javelin anti-tank missiles have been the mainstay in Ukraine to defeat Russian armor. Currently, inventories are considered low. “The United States has sent about 40 percent of its inventory to Ukraine, the maximum the Pentagon planners are comfortable with,” the Center for Strategic and International Studies reported. Furthermore, the inventory of Stinger/Avenger shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles is deemed “Extremely limited.”

A robust, ready defense industrial base is crucial to the US being able to engage a peer-capable enemy like China or Russia. With inventories of weapons and ammunition being stressed, the impact of conventional deterrence is questionable. Wartime capability means getting to the action – but it also means having weapons to use and ammunition to fire.

The views expressed are those of the author and not of any other affiliation.