War is hell. Everyone knows it, especially those who have been in the midst of it. But not all wars are created equal. World War II was considered a “good” war, Vietnam was not. The post-9/11 war in Afghanistan was most often labeled good, while the Iraqi War was not. And as we examine the ongoing bloody conflicts in the Middle East and Europe, is it possible to establish durable parameters for which type of war is justified and which is not? This is where so-called just war theory comes in. Many attempts have been made by political and military leaders over hundreds of years to define a morality common to all humans and what thus constitutes a just or unjust war. And several of these principles of military ethics have stood the test of time.

Everyone from military leaders to theologians, ethicists to policymakers, has studied and debated various iterations of just war theory over the years. The analysis is divided into two basic categories: jus ad bellum, meaning the right to go to war, and jus in bello, meaning right conduct in war. They are based on the notion that all war is terrible, but it is less so with a clear defensible purpose and proper conduct which can prevent the type of atrocities and war crimes that have taken place in Israel and Ukraine.

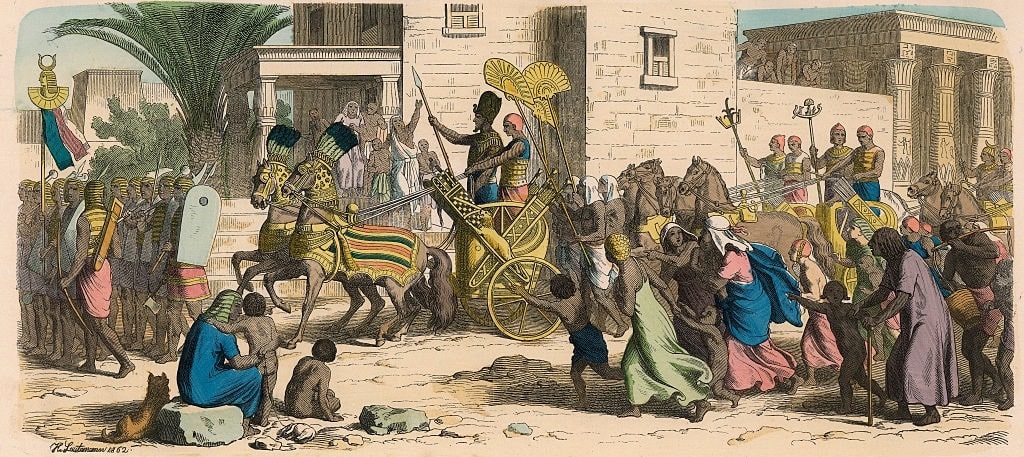

As far back as ancient Egypt, rulers and governments have attempted to distinguish between wars of necessity and wars of choice, wars of offense and those of defense, wars where one side possesses superior firepower and the other is outmanned and/or outgunned. Though just war theory was at first used to rationalize the actions of a Roman emperor, it has since proven useful in distinguishing between those who start wars and those who fight to defend themselves, between legitimate and illegitimate engagement, between good and evil.

The Long History of Just War Theory

(Photo by Stefano Bianchetti/Corbis via Getty Images)

These time-tested principles of just wars developed over the course of multiple empires and civilizations represent the closest thing we have to an objective measure of the relative guilt of parties engaged in war. The attackers in the two conflicts currently raging in the eastern hemisphere are Russia, and Iran – through its multiple proxies, primarily Hamas – and the attacked are Ukraine and Israel. Both wars were unprovoked. The expansion of NATO was hardly a legitimate rationale for invading a mostly peaceful neighbor and murdering thousands of innocent civilians. And the savage slaughter of some 1,400 Israelis by Hamas was equally unprovoked, no matter how many Hamas apologists try to spin it with their talk of Israeli occupation.

The Egyptians’ just war beliefs were quite different than those of modern times. They established the pharaoh as a divine office – much like the Pope – commanded to carry out the will of the gods (thus justifying almost any of his actions) and declared the inherent superiority of the Egyptian people and state (not dissimilar to Germany during World War II). Since then, the just war theory has moved in an opposite direction with conventions and treaties based on agreed-upon moral obligations regarded as innate to the human species, most prominently the Geneva Conventions. Most major civilizations that followed Egypt, including the Hindus of India, East Asians, and the rulers of Ancient Greece and Rome, refined the theory to something well beyond simply asserting that their supreme ruler was to be treated as God, and therefore inerrant in all his beliefs and actions. The Romans asserted that war should be a last resort waged only in order to restore peace, by repelling an invasion, or retaliation for the breach of a treaty, and that any declaration of war must be ritualized by the priests of ancient Rome. Aristotle argued that the military is a necessity, but for the purpose of self-defense, not conquest.

Christian tradition on just war theory dates back to the fifth century, when St. Augustine held that people should not use violence as a first resort, but also that God has given authority – and a sword – to government for a reason. He invoked Romans 13:4: “… for he is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer.” In actually introducing the term just war, Augustine wrote, “But, say they, the wise man will wage Just Wars … No war is undertaken by a good state except on behalf of good faith or for safety.”

Centuries later, St. Thomas Aquinas reinforced the Christian doctrine of just war in his Summa Theologica, asserting that it was not necessarily a sin to wage war – the Old Testament is replete with references to God commanding his people to show His/their enemies no mercy. But he sets out several conditions that must be met to justify war: it must be waged by a rightful sovereign; it must be provoked by some demonstrable wrong committed by the enemy; warriors must be motivated to promote good and avoid any instinct for evil; injustice should not be tolerated for the singular purpose of avoiding war; and the good intention of a moral act could justify collateral damage, i.e. the death of innocents in wartime.

Some morality markers are self-evident to the unjaundiced eye. Israel famously protects its citizens at all costs. Islamists use theirs as human shields – even babies. Putin’s troops mow down masses of civilians standing in their way. Could anything be more despicable, more repellent to what most consider a baseline level of human morality? Almost any way you cut and slice it, history’s long-standing just war theories deliver an unequivocal guilty verdict to Vladimir Putin, the mullahs of Iran, and the Islamist terrorists who committed acts so savage that several members of the Israeli Knesset had to ingest anti-anxiety medication in order to view the compiled footage of unspeakable Hamas atrocities against innocent, unarmed Israelis. At the same time, almost any iteration of legitimate just war theory will vindicate the actions of Israel and Ukraine. The empty-headed anti-Semitic protesters flooding our streets and college campuses might not like to hear it, but the rest of civilization must.