Another Biden nominee begins the confirmation hearing process today, April 20. The vote will likely fall along party lines, as it usually does. That a contentious confirmation process is expected just goes to show how divided the partisan Congress has become. But is that a blessing in disguise? As history has demonstrated, it’s when both sides work together that freedom-loving Americans should worry.

Julie Su – A Paragon of California

A paragon of California – that’s how both sides seem to see Julie Su, Joe Biden’s current pick to lead the Department of Labor. But that means different things to different people. Supporters see promise in her career in the Golden State, but detractors fear a Californiazation – though some prefer the term Californication – of the nation. “California is not a model to emulate for the rest of the country,” Sen. Richard Burr (R-NC) said in 2021 after voting for Biden nominee Marty Walsh for Labor Secretary, but against Su for the deputy spot. Su’s first confirmation was approved by a party-line vote of 50-47. Pundits expect this round will be even more difficult.

With some Democrats remaining non-committal on whether they’ll support her, Su’s fate in the Senate is far from pre-determined. The fight, however, is about as predictable as death and taxes. And there’s a good reason to be glad of that political divide in such a closely split Senate.

The Partisan Congress – Nothing New Under the Sun

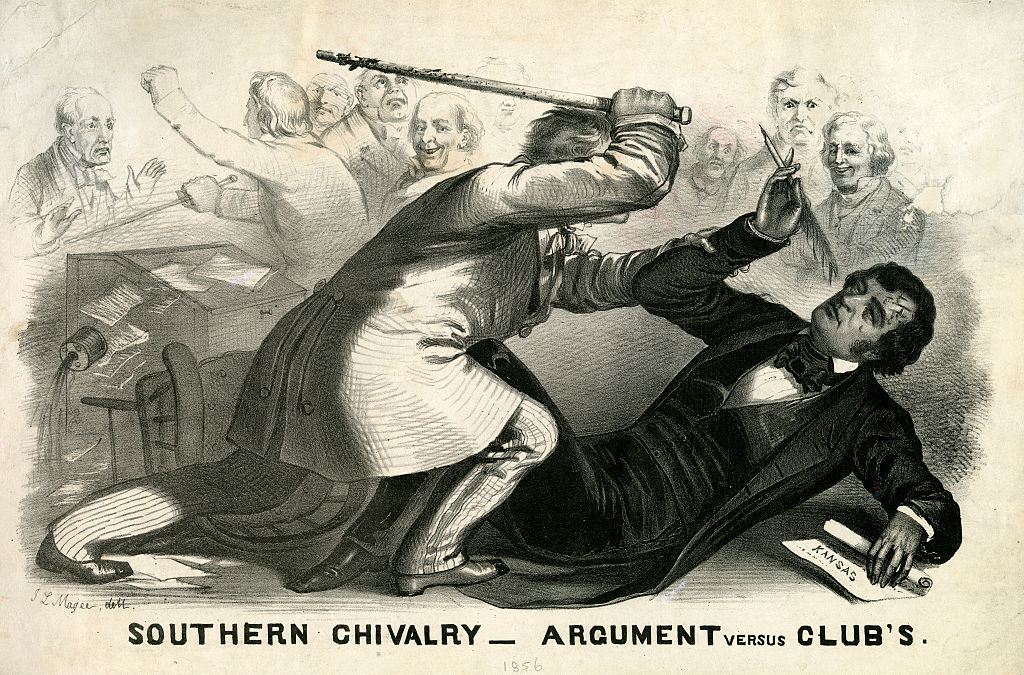

Caning of Sen. Sumner, Lithograph (Photo by New York Historical Society/Getty Images)

We tend to think of tit-for-tat politics and heated debates turning nasty as recent developments. They are not. In February of 1798, Federalist Congressman Roger Griswold of Connecticut beat Democratic-Republican Matthew Lyon of Vermont with a hickory walking stick in the House chambers.

In a far more famous example, Republican Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts gave a speech in 1856 in which he called Sen. Stephen Douglas, an Illinois Democrat, a “noise-some, squat, and nameless animal … not a proper model for an American senator.” He went on to mock South Carolina Democrat Andrew Butler’s character and taste in women. Rep. Preston Brooks, a kinsman of Butler’s, beat Sumner in the head viciously with a cane. The most infamous floor brawl in the history of the US House of Representatives broke out in February of 1858 and involved more than 30 members. Sergeant-at-Arms Adam J. Glossbrenner had to threaten to arrest anyone who didn’t settle down. In short, the “good old days” of bipartisan, peaceful coexistence are and always have been a myth.

Be Careful What You Wish For

The House of Representatives will almost always go the way of the majority. No matter how slim the margin, the dominant party can pass its legislation almost at will. But things are different in the Senate. Generally speaking, for a bill to clear the upper chamber, it needs to be something that at least a handful of minority-party senators can sign on to. Otherwise, shy of some shenanigans like convincing the Senate Parliamentarian to reinterpret the rules for something like budget reconciliation, most bills are dead in the water.

But there have been numerous times when both sides played ball, and not just to declare holidays, rename post offices, or virtue signal through powerless “sense of Congress” resolutions. Think instead about bloated budgets and debt ceiling increases that drive the nation more into debt and knee-jerk political reactions. Not every bipartisan bill has been a staggering blow against liberty, but some of the biggest examples throughout the nation’s history certainly were.

In 2001, barely a month after the terrorist attack in September, the Senate passed the USA PATRIOT Act of 2021 98-1, with one other not voting. It doesn’t get much more bipartisan than that. The Department of Justice said of the new law that it “improves our counter-terrorism efforts in several significant ways.” Be that as it may, it also significantly grew the police state in America and ran afoul of Benjamin Franklin’s warning about trading liberty for temporary safety. The Act gave law enforcement and executive agencies sweeping powers of surveillance all in the name of keeping us secure against terrorists – but as famous whistleblower Edward Snowden demonstrated, the federal government became obsessed with “making every conversation and every form of behavior in the world known to them,” as he told The Guardian in 2013.

In 2001, barely a month after the terrorist attack in September, the Senate passed the USA PATRIOT Act of 2021 98-1, with one other not voting. It doesn’t get much more bipartisan than that. The Department of Justice said of the new law that it “improves our counter-terrorism efforts in several significant ways.” Be that as it may, it also significantly grew the police state in America and ran afoul of Benjamin Franklin’s warning about trading liberty for temporary safety. The Act gave law enforcement and executive agencies sweeping powers of surveillance all in the name of keeping us secure against terrorists – but as famous whistleblower Edward Snowden demonstrated, the federal government became obsessed with “making every conversation and every form of behavior in the world known to them,” as he told The Guardian in 2013.

The Second Amendment has also been no stranger to intrusion:

- The National Firearms Act of 1934 was a direct response to gang violence – which, itself, was the result of the doomed government policy known as Prohibition. It cleared the Senate by a voice vote.

- Initially inspired by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, the Gun Control Act of 1968 was passed through the Senate with the help of 31 Republicans.

- There were 16 Republicans who voted to pass to the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act Federal Firearms License Reform Act of 1993, which created the national criminal background check system, created the list of prohibited persons, and required licenses for firearm dealers. Jim “the Bear” Brady had been Reagan’s White House press secretary. He was permanently disabled in the 1981 attempt on the president’s life.

- Nine Republicans then helped the Democrats pass the infamous assault weapons ban of 1994.

A decades-spanning series of tragedies that resulted in knee-jerk reactions by members of Congress who felt a need to “do something,” even if that meant infringing upon a right long recognized as uninfringeable since the founding of the nation.

(Photo by congress.gov via Getty Images)

More recently, bipartisan action has brought us a new federal gun control law. While the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act didn’t throttle back the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms quite as thoroughly as the older examples mentioned before, it still meant broader background checks, more people disarmed, and a slush fund to pay states to implement red-flag laws. While Biden didn’t see his full Build Back Better dream become a reality, bipartisan action brought about the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which still included a progressive wish list of green spending.

The base pay for a member of Congress is $174,000 a year. Across the Senate and House, including non-voting delegates, there are 541 elected members of Congress. That comes out to no less than $97.6 million a year before even counting the extra pay for leadership positions or all the congressional staffers. As expensive as Congress is, it’s tempting to complain when they don’t do what most folks perceive their job to be. But considering the net result of all these years of legislation, committing more and more tax dollars to various causes and growing the leviathan the federal government has become, perhaps the American people are far better off when the partisan Congress doesn’t work. Whatever we’re paying them today to bicker and argue between themselves, it pales in comparison to what we’ve lost since the founding.