ACADEME, n. An ancient school where morality and philosophy were taught.

ACADEMY, n. (from academe). A modern school where football is taught. — Ambrose Bierce

Have US colleges and universities gotten sidetracked or fallen entirely off the rails? It seems that wayward priorities, avoidance of treating mental health issues, and misaligned mission statements have left graduates unprepared. Based on a six-year study conducted by Harvard colleagues Howard Gardner and Wendy Fischman, American colleges could take steps to better prepare graduates for life beyond the classroom.

The Real World of College Study

(Photo by Ben Hasty/MediaNews Group/Reading Eagle via Getty Images)

The study began in 2013 and involved more than 2,000 subjects, half of which were students. The remaining interviewees were a mix of parents, faculty, administrators, and college alumni. A diverse combination of schools – from highly particular liberal arts colleges down to less selective state schools – were included in the study.

The students were asked 40 non-specific questions encompassing life on campus, both in and out of the classroom. A three-point analytic scale called HEDCAP (higher education capital) was created to gauge the answers and determine the pupil’s ability to discuss critical issues and take on and dissect challenges. The results displayed a pattern of improvement as the students progressed from the first year to seniors, but the overall scores were low. In fact, less than a third of the participants who graduated scored at the top of the scale.

What They Found

Gardner and Fischman spent two years analyzing the information they had gathered. Their conclusions did not fault the students but instead the colleges and universities. The team discovered that, though the scholars value professionalism, they did not apply ethical and moralistic behaviors to their schoolwork. For example, many students admitted to lying about their methods in research and journalistic source-citing. Basically, the kids felt that hard and honest work was something they could apply later in life but did not find necessary to get through college.

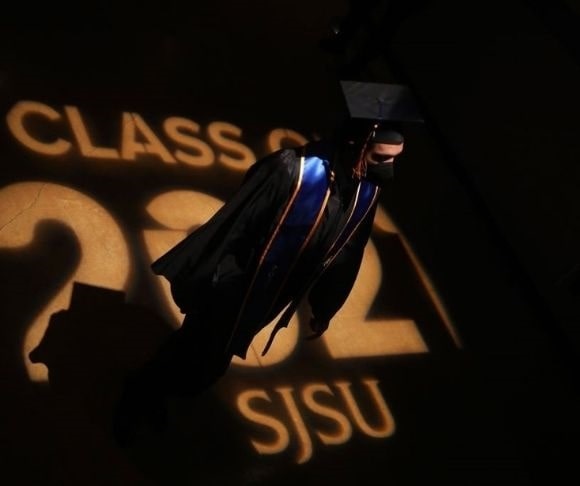

(Aric Crabb/MediaNews Group/East Bay Times via Getty Images)

The research raises concern that students are not encouraged to think critically or use their time in school to explore new areas, but more to comply with the structure of the university and settle into their carved-out space in the occupational world. Possibly one of the more eye-opening and concerning discoveries was that many students found it difficult to name a book they would recommend.

“In one example that the authors noted with particular disgust, many students could not name a book they would suggest to others at their institution. Those books that were recommended were typically high school-level texts, such as To Kill a Mockingbird or The Catcher in the Rye, or books typically read at even lower school grades.”

Where US Colleges Have Gone Wrong

Using the data, the authors were able to identify potential sources of the problem. First, they believe that college mission statements should be more honest and direct and not just look good on paper. Gardner said, “Part of my answer would be truth in advertising. If you claim you’re expanding the mind, exposing people to lots of different fields and giving them the chance to explore, then you need to do that.”

Second, schools offer too many extracurricular activities, putting too much value on sports and other non-academic events. Students are overwhelmed with the variety of options to choose from, causing their priorities to wander away from what is truly important: their education and personal growth.

Third, intense pressure to get good grades and make decisions early on about what job they want causes anxieties and unnecessary strain on the students. The researchers believe a course schedule that allows for broader thinking, self-expression, exploration, and openness to change would be beneficial to student growth and enhancement.

Fourth, Gardner and Fischman are concerned that kids with mental health issues are not monitored as closely as they should be. Throughout the research portion of their mission, they found that many students felt out-of-place, leading to intensified symptoms and crippling their ability to fully embrace and capitalize on the college experience.

Fourth, Gardner and Fischman are concerned that kids with mental health issues are not monitored as closely as they should be. Throughout the research portion of their mission, they found that many students felt out-of-place, leading to intensified symptoms and crippling their ability to fully embrace and capitalize on the college experience.

Finally, graduates are sent into the world and workforce with just a minimal amount of knowledge that pertains to their major and does not promote job enhancements or prepare them for volatility in the workplace. Gardner and Fischman used the information to design and create courses and other reparative interventions at Harvard and nearby colleges to help invigorate students’ minds and broaden their cognitive skills.

Read more from Kirsten Brooker.