On October 21, former Trump campaign strategist Steve Bannon was sentenced to four months in prison – and ordered to pay a $6,500 fine – after the Jan. 6 Committee held him in contempt of Congress. Not since the 1950s has anyone been incarcerated for this particular transgression, though many since then have been held in contempt by various congressional bodies. So, why is Bannon going to prison, assuming his appeal is unsuccessful? One can only speculate. The extraordinary nature of a prison term being handed down for contempt can hardly be overstated. To some, it will smack of the heavy-handedness with which Democrats and the authorities have dealt with anyone associated with and loyal to the 45th president.

For proper context, though, it should be noted that Bannon got off with a lighter punishment than prosecutors wanted. Still, contempt of Congress is generally not something for which anyone goes to prison. Bannon, unlike Barack Obama’s attorney general, Eric Holder – who was held in contempt for refusing to hand over documents relating to Operation Fast and Furious – did not have the luxury of a sympathetic Department of Justice. In recent decades, the DOJ has declined to prosecute government officials from both Democratic and Republican administrations who were held in contempt by congressional committees controlled by the opposing party. Officials from both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations benefited from that very discretion the DOJ is entitled to exercise. Steve Bannon, then, was perhaps the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time, one might say.

For proper context, though, it should be noted that Bannon got off with a lighter punishment than prosecutors wanted. Still, contempt of Congress is generally not something for which anyone goes to prison. Bannon, unlike Barack Obama’s attorney general, Eric Holder – who was held in contempt for refusing to hand over documents relating to Operation Fast and Furious – did not have the luxury of a sympathetic Department of Justice. In recent decades, the DOJ has declined to prosecute government officials from both Democratic and Republican administrations who were held in contempt by congressional committees controlled by the opposing party. Officials from both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations benefited from that very discretion the DOJ is entitled to exercise. Steve Bannon, then, was perhaps the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time, one might say.

What is Contempt of Congress?

Like impeachment, contempt of Congress can be a somewhat arbitrary thing. The Constitution does not explicitly confer upon Congress the power to hold someone in contempt, but that authority is implied. Perhaps the easiest explanation of the rationale is provided by Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute: “[S]uch power is considered implied because without it, Congress could not effectively carry out its duties.” Congress can investigate matters if there is some legislative purpose. Obviously, those investigations require the gathering of documents and the testimony of relevant individuals. The Supreme Court has recognized the authority of Congress to hold in contempt those who refuse to comply with subpoenas, hand over documents, “or who, having appeared, refuses to answer any question pertinent to the question under inquiry.” That last part seems somewhat amusing, though, considering the number of times witnesses have refused to give straight or clear answers during congressional hearings – and on some occasions refused to answer the question at all.

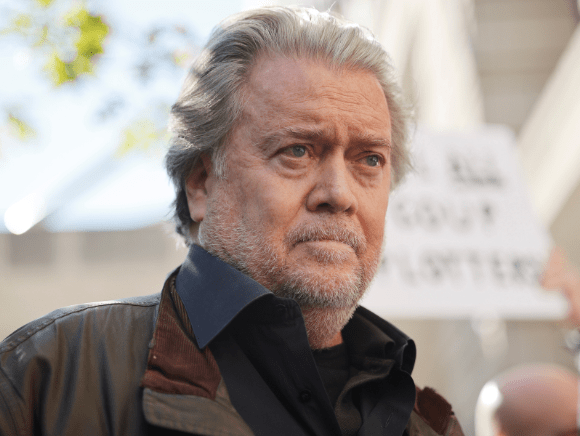

Steve Bannon (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The Supreme Court has also recognized, however, that the investigative powers of Congress are limited. Matters of law enforcement, for example – rather like the issue of the Jan. 6 Capitol unrest – are not within the purview of Congress. Those are matters for the executive branch and for law enforcement agencies. That said, members of Congress have reason to claim jurisdiction in the case of Jan. 6. The very building in which they conduct business was, after all, under siege. That, of course, strikes at the heart of a debate over the committee’s legitimacy and, by extension, Bannon’s contempt citation.

The last time anyone went to prison for contempt of Congress was when, in 1947, hearings began on the possible infiltration of the movie industry by communist sympathizers. In 1948, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) held 10 movie writers, directors, and producers – known as the “Hollywood Ten” – in contempt for refusing to tell the committee whether they were communists. Eight of the men were sentenced to one year in prison and the other two received six-month terms.

What Next for Steve Bannon?

The former media executive who became Chief Strategist and Senior Counselor to the President had been one of Donald Trump’s staunchest allies, though friction between the two emerged during the course of the Trump administration. His fall from grace was previously documented by Liberty Nation, but so was a prediction of his possible re-emergence. Bannon announced his intention to appeal the conviction outside the courthouse in a brief but fiery address to reporters. “On November 8th,” Bannon said, “they’re gonna have judgment [sic] on the illegitimate Biden regime and quite frankly, Nancy Pelosi and the entire [Jan. 6] committee. And we know which way that’s going.” Clearly relishing his moment back in front of the microphones – having made no public statements during his trial – Bannon went so far as to suggest that “the Biden administration ends on the evening of the eighth of November” and that Attorney General Merrick Garland would be removed from office, though he did not elaborate on how or why that would come to pass.

Regardless of whether one believes Steve Bannon’s conviction or sentence was just or appropriate, it will likely do him no harm to serve a brief prison sentence. On the contrary, it may even raise his standing among hardcore Trump supporters who could come to see him as something of a martyr. The Jan. 6 Committee has achieved little except to harden the resolve of Mr. Trump’s most loyal followers and Bannon’s incarceration may well serve, even if only symbolically, as another reason for them to continue the battle they see as being between American patriots and the establishment. Trump’s opponents may view it as a small victory but, to Steve Bannon and to MAGA Country, this will be yet one more reason why America First populism must be more rigorously pursued, and the Washington Swamp drained.