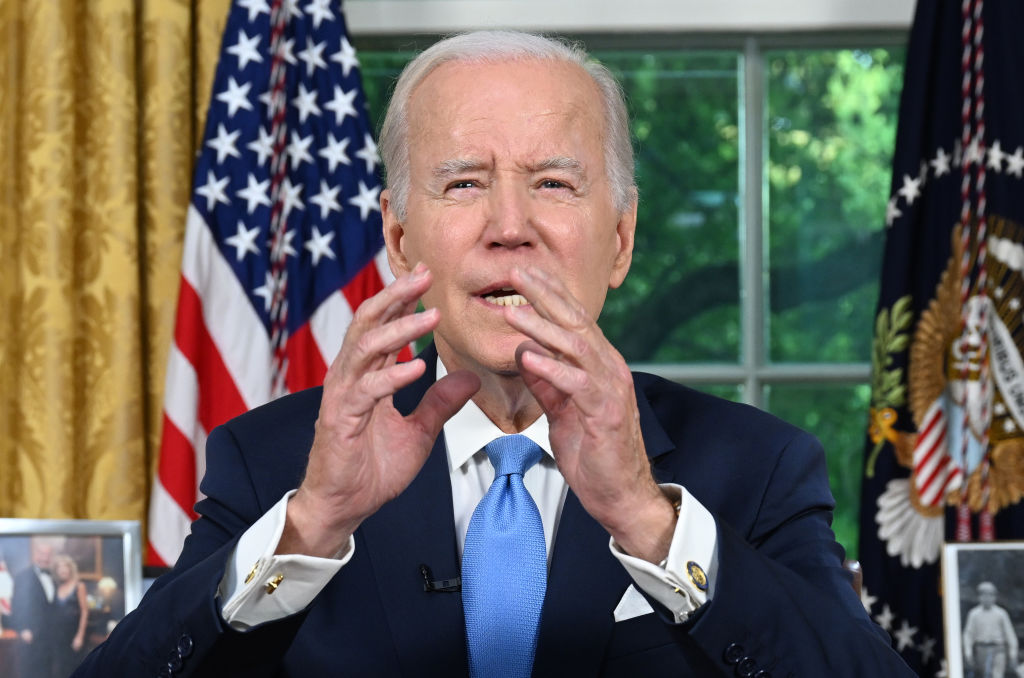

President Joe Biden spoke to the nation Friday night in his first ever primetime Oval Office address to tout the latest debt limit deal. The Fiscal Responsibility Act, which Biden plans to sign later today, cleared the Senate 63-36 Thursday, June 1, after passing 314-117 in the House a day earlier. Unlike some of the bills the president has lauded as such, this one really did receive bipartisan support in both chambers – but it saw bipartisan blowback, as well.

Unity, Is That You?

“Our teams were able to get along, get things done, were straightforward with one another, completely honest with one another, respectful with one another,” the president said during his address from the Oval Office. “Both sides operated in good faith. Both sides kept their word.” Biden went on to commend Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY), Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY). It was a great “unity” moment for the president, and an even better launchpad for him to start patting himself on the back for all of his accomplishments so far since taking the White House.

Have we finally found that elusive unity Biden keeps going on about? The debt limit deal and the president’s words certainly suggest it. But as Liberty Nation Economics Editor Andrew Moran wrote shortly after the Senate’s vote, “the more things change, the more they stay the same. This was true on June 1, 2023, and it will still be the case on Jan. 1, 2025.” Just as the passage of this act won’t fix the economy, it also doesn’t represent some miraculous healing of the ideological rift in this nation.

Bipartisan on Both Ends

There’s no need to look any further than the president’s own speech to see the hole in his unity façade. Biden went from commending the cooperation in Congress to criticizing Republicans for defending what he called special interest tax loopholes, then took the opportunity to stump for his own presidential campaign. “But I’m going to be coming back,” he said. “And with your help, I’m going to win.”

A deeper look at the vote totals shows the Fiscal Responsibility Act really was bipartisan on both ends. That 314-117 House vote Wednesday breaks down to 149 Republican “Ayes” to 71 “Noes,” but the GOP wasn’t the only party divided. Democrats, while not as split as their counterparts across the aisle, voted 165-46 for the bill. The procedural vote earlier in the day that paved the way for that final passage also saw significant opposition from both sides, with some of the Democrat “Ayes” flipping from “Noes” at the last moment to save the day.

A deeper look at the vote totals shows the Fiscal Responsibility Act really was bipartisan on both ends. That 314-117 House vote Wednesday breaks down to 149 Republican “Ayes” to 71 “Noes,” but the GOP wasn’t the only party divided. Democrats, while not as split as their counterparts across the aisle, voted 165-46 for the bill. The procedural vote earlier in the day that paved the way for that final passage also saw significant opposition from both sides, with some of the Democrat “Ayes” flipping from “Noes” at the last moment to save the day.

The bill required 60 votes to pass in the Senate, so a total of 63 “Yeas” is far from a landslide victory. And it wasn’t just Republicans who opposed in the upper chamber, either. The Senate’s 63-36 vote breaks down to 46 Democrats voting for the act to five against and 17 Republicans voting for it to 31 against.

Senators Ed Markey (D-MA), Jeff Merkley (D-OR), John Fetterman (D-PA), Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) were the five from the left who voted against the bill, though their reasons were vastly different from those of their fellow opposers across the aisle. While Republicans typically rejected the deal because it doesn’t cut back on the Leviathan’s diet quite enough, the more progressive Democrats felt it goes too far at the people’s expense. “I will be voting no on the debt limit deal because you do not do deficit reduction on the backs of Americans who are already struggling,” Sen. Sanders tweeted Wednesday, May 31. Sen. Fetterman accused the GOP of being “more obsessed with hurting poor people than holding banks accountable” on Twitter. “Time and time again, Congressional Republicans show us that they’d much rather help giant corporations than working people,” Sen. Warren said after her “no” vote. “I’m done being surprised, but I’m not done fighting to stop them.” What none of these senators mentioned, of course, is that the deal is as much Biden’s as McCarthy’s.

The Battle Beyond the Vote

The political blowback from the Fiscal Responsibility Act doesn’t stop now that the votes are over. As LN reported earlier, Speaker McCarthy’s leadership role might be in jeopardy. No action has been taken against him yet, but a few House Republicans have brought up calling a vote to vacate McCarthy as speaker. Thanks to the rules the California Republican agreed to in exchange for enough Freedom Caucus votes to become speaker, that once again only requires a single representative putting forth such a motion.

Should it go to the floor, can McCarthy count on enough of those 71 GOP no votes to still support him? He might not have to. Back as far as mid-May – before Biden and McCarthy had hammered out the current deal – dozens of House Democrats told their Republican colleagues that they could provide the votes to protect the speaker if his own party tries to oust him. As first reported by Politico on May 16, the group remains informal and isn’t officially sanctioned by party leadership, but consists of roughly 40 Democrats. The Freedom Caucus is understood to have about 40 members as well, which presents an interesting twist in the plot, should a motion to vacate come up.

(Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

But McCarthy isn’t the only lawmaker facing pushback from his own party. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) voted for the new bipartisan debt limit bill, and doing so meant voting for the West Virginia pipeline deal he fought so hard to have included. More progressive Democrats and environmental groups outside of Congress say it will lead to many more years of dependency on fossil fuels, and it will do so by circumventing the normal procedures.

“Singling out the Mountain Valley Pipeline for approval in a vote about our nation’s credit limit is an egregious act,” said Peter Anderson, Virginia policy director for Appalachian Voices. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) – along with several House Democrats – tried and failed to strip the act of Manchin’s pipeline deal.

No one got everything they wanted, and that’s the nature of compromise, as the president pointed out in his Friday night address. But that doesn’t do justice to just how fierce and, yes, bipartisan, the opposition was, as well. Nor does it account for the president’s own refusal to negotiate until the last minute – even with a debt limit and spending cuts deal already passed by the House. And of course, one can’t discount the weight of the early June default deadline in pushing many who certainly didn’t “get everything they wanted” into caving under pressure. Yes, the Fiscal Responsibility Act was Biden’s and McCarthy’s deal, and it did receive bipartisan support in Congress. But it’s a far cry from the national moment of unity the president presents it to be.