The US Senate Banking Committee held a hearing on May 16 that featured the men behind the banking crisis curtain: former Silicon Valley Bank CEO Gregory Becker, Signature co-founder Scott Shay, and former Signature president Eric Howell. Lawmakers touched upon a wide range of areas, but one of the major talking points was tackling bank CEO compensation, especially when financial institutions crumble. With both sides of the aisle open to reining in what executives of failed banks earn, this might be the newest regulatory push in Washington. But will it prevent more banking turmoil in the future?

Bank CEO Compensation Scrutinized

In 2022, Becker’s total compensation was valued at about $9.9 million. Former Signature CEO Joseph Depaolo, who did not appear before the Senate due to health concerns, earned nearly $9 million in 2021. First Republic CEO Michael Roffler enjoyed a $900,000 base salary and a maximum annual incentive bonus package of $2.95 million last year. Were the heads of these regional banks paid too much? Democratic and Republican lawmakers in both chambers presented the case that the business leaders did not earn this money, considering the putrid health of these companies.

“Both of your banks pushed up your stock prices and your own executive compensation – but didn’t address the glaring risks from customer and industry concentration,” Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) said in his opening remarks. “When you put other people’s money and our broader economy at risk, there must be accountability for that level of mismanagement.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) repeatedly asked the witnesses how much they would contribute to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) after SVB and Signature cost it about $20 billion. None of the executives pledged to donate their salaries to the DIF. But this was part of a broader point the Massachusetts senator was making: these individuals will lobby for weaker banking regulation, which, according to Warren, devastates the banking system and harms the economy, allowing these people to make a fortune and walk away scot-free.

“If we don’t fix it, every CEO for these multibillion-dollar banks will keep right on loading up on risks and blowing up banks, and everybody else is going to have to pay for it,” she said.

Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA) struggled to utter a similar idea, arguing that mismanaged banks could hurt the financial sector and destroy the economy. He also strove to suggest that there should be working requirements for executives who receive bailouts from the federal government comparable to the work criteria for welfare recipients (because it was hard to understand his question, the witnesses did not provide answers).

Becker received a grilling from Sen. John Kennedy (R-LA), who accused the CEO of not purchasing hedges because it would have affected his pay. “So, if you bought hedges, you’d have less money,” Kennedy said. “If you’d made less money, that would have affected your bonus, wouldn’t it?” In usual Kennedy fashion, the senator provided a cherry on top of his allotted time:

“You made a really stupid bet that went bad. This was bone deep, down to the marrow stupid. You put all your eggs in one basket. Unless you were living on the International Space Station, you could see that interest rates were rising, and you weren’t hedged.”

The Legislative Pursuit

Joe Biden (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

In March, four senators – Warren, Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV), Sen. Mike Braun (R-IN), and Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) – introduced legislation that would claw back compensation from failed bank executives. The bill would extend the authority to the FDIC to collect all or part of the compensation bank executives received in the five years before the entity’s collapse. Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-MI) also revealed during that May 16 House Financial Services Committee hearing that she is crafting a bill to target bank CEO compensation. In addition, Federal Reserve Vice Chair for Supervision Michael S. Barr confirmed that regulators are assessing a similar regulatory proposal.

Following the banking meltdown, President Joe Biden encouraged Congress to allow regulators to confiscate compensation “when banks fail due to mismanagement and excessive risk-taking.”

This is a compelling discussion for economists with a libertarian bent. On the one hand, it is safe to say that many libertarian-leaning economists disagreed with bailing out SVB and Signature and these institutions’ depositors. But, on the other hand, if taxpayers are rescuing these companies, should representatives insert specific measures that they think would prevent a contagion event? Perhaps this is what occurs when Pandora’s box is opened or when the free market accepts a Faustian bargain: Government intervention begets government intervention.

At the same time, there has been a real-world example of what happens when public policymakers install a feel-good measure. In 2013, the Swiss government launched an executive pay initiative that restricted salary and banned bonuses. One of the affected banks? Credit Suisse. The European giant had previously confirmed that this policy was one of the hurdles to attracting and retaining talent, going as far as identifying it as a risk to the bank’s long-term health. Lo and behold, the 170-year-old bank crumbled due to poor management.

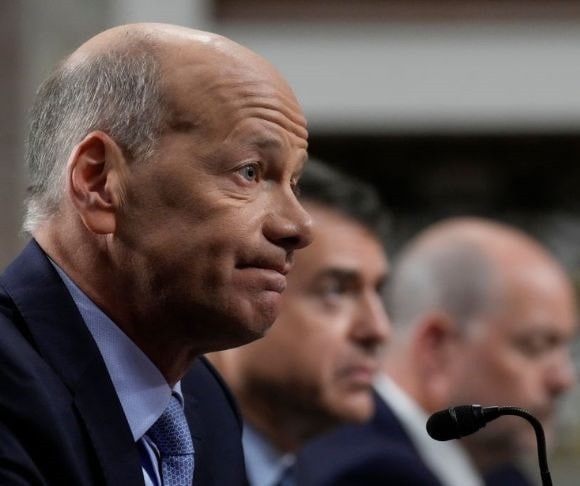

Silicon Valley Bank CEO Gregory Becker (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Moreover, following the 2008-2009 financial crisis, the National Bureau of Economic Research published a paper that concluded there was no link between bank CEO compensation and failures. In fact, according to Professors Ruediger Fahlenbrach (Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne) and Rene M. Stulz (Ohio State), “banks where CEOs had better incentives in terms of the dollar value of their stake in their bank performed significantly worse than banks where CEOs had poorer incentives.”

Good Intentions

On the surface, the Democratic and Republican lawmakers might have good intentions by targeting bank CEO compensation. However, as the saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Despite executive pay being lambasted as one of the ailments of free-market capitalism, there is a reason why corporations and their shareholders are willing to pay CEOs millions of dollars in salary or stock options: They want the best person for the job to maximize profits, boost the stock, and ensure the long-term health of the company. Sometimes it works out, like Tim Cook of Apple and Bob Iger of Disney. Sometimes it does not, such as Steve Ballmer of Microsoft and Dick Fuld of Lehman Brothers.

Critics will assert that the United States maintains a quasi-capitalist economy. But how can it be a free market when automobile companies are bailed out with taxpayer dollars and banks’ losses are socialized? Indeed, it is the former President George W. Bush philosophy of abandoning free market principles to save the free market. But when this happens, the private sector must brace for politicians and bureaucrats continuously being busybodies, like the old lady living in the corner house who calls the police because the neighborhood children are selling lemonade without a license.