On May 2, the US Supreme Court released a ruling in Shurtleff et al. v. City of Boston et al. Boston refused to allow a group called Camp Constitution to fly the Christian Flag on the third flagpole at City Hall during an event back in 2017 – despite having allowed many other groups to fly their own flags, including the Pride Flag, since 2005. Harold Shurtleff, Camp Constitution’s director, sued, claiming the city had violated the First Amendment right to free speech. And all nine justices of the Court agreed.

This decision overturned the work of the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, which upheld the district court’s decision to side with the City of Boston. Join Liberty Nation Legal Affairs Editor Scott D. Cosenza, Esq. and Editor-at-Large James Fite as they explore this ruling and what it means for the case, the courts, and the application of the First Amendment in general.

This decision overturned the work of the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, which upheld the district court’s decision to side with the City of Boston. Join Liberty Nation Legal Affairs Editor Scott D. Cosenza, Esq. and Editor-at-Large James Fite as they explore this ruling and what it means for the case, the courts, and the application of the First Amendment in general.

James Fite: The Supreme Court has overturned a lower court’s ruling that validated the City of Boston’s refusal to allow Camp Constitution to fly the Christian Flag at City Hall, but this was back in 2017. Now that SCOTUS has ruled against that action, what is the immediate remedy?

Scott D. Cosenza, Esq.: In this case, and cases like it, the Supreme Court sends it back to the Federal District Court from which it originated for further proceedings consistent with the ruling. Since the City of Boston violated the free speech rights of Camp Constitution, the group will likely be awarded money damages. If Boston had not canceled the guest flag program, I would expect the district court also to order the city to fly the flag.

JF: If flying the Christian Flag would be government speech – as the circuit court ruled – would flying the Pride Flag also be government speech?

SDC: Yes. Boston argued that when it flew flags, that constituted government speech. The city’s legal argument was that since the city was the one speaking, the city was in fact forbidden from flying it, rather than required to do so, as the Supreme Court has now ruled. Our constitutional law prohibits government from endorsing a religion, but not the messages likely meant by a “Pride Flag.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s brief concurring opinion seemed written to make one point:

“This dispute arose only because of a government official’s mistaken understanding of the Establishment Clause … So Boston granted requests to fly a variety of secular flags, but denied a request to fly a religious flag. As this Court has repeatedly made clear, however, a government does not violate the Establishment Clause merely because it treats religious persons, organizations, and speech equally with secular persons, organizations, and speech in public programs, benefits, facilities, and the like.”

(Photo by Daniel Knighton/Getty Images)

JF: In the official ruling from SCOTUS, Pride Flag is treated as a proper noun. There are several pride flags, but the LGBT Pride Flag designed by Gilbert Baker, also called the Rainbow Pride Flag, is probably the most recognizable, and it was adopted in 1978. The Court said the banner Shurtleff wanted to display was “what he described as the ‘Christian flag.’” The Christian Flag is used officially by many churches and Christian groups. It has been widely used unofficially since 1897 and was officially adopted by the Federal Council of Churches in 1942. Christian Flag, much like Pride Flag, is the name of a flag not recognized by any government but still in official use by some groups. So why doesn’t it get the same treatment?

SDC: That’s a great question for Justice Stephen Breyer, who wrote the opinion of the Court. Woke language has made its way to the Court for sure. We’ve seen at least one justice now capitalizing the “b” in “black,” when she did not last year.

JF: We know the ruling says Boston violated the rights of Camp Constitution, and that was unanimous. There were three opinions written besides Breyer’s, however. You discussed Kavanaugh’s – what did the other two say?

SDC: Justice Samuel Alito wrote a lengthy concurrence objecting to Breyer’s three-factor analysis of whether speech is government speech or private speech. Alito wrote, “the real question in government-speech cases: whether the government is speaking instead of regulating private expression.” He ripped Breyer’s factor analysis to shreds:

“The Court concludes that two of the three factors—history and public perception—favor the City. But it nonetheless holds that the flag displays did not constitute government speech. Why these factors drop out of the analysis—or even do not justify a contrary conclusion—is left unsaid.”

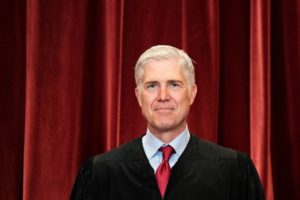

Justice Neil Gorsuch (Photo by Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images)

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in large part to criticize a 1971 case called Lemon v. Kurtzman, which used a multi-factor test to evaluate speech. “[W]hy did Boston still follow Lemon in this case? Why do other localities and lower courts sometimes do the same thing … ?” he wrote. “[I]t’s hard not to wonder whether some simply prefer the policy outcomes Lemon can be manipulated to produce.” And he continued, “for some, that may be more a virtue than a vice.”

Gorsuch tore into the city and others who want to use the First Amendment as weapon against free speech, as Boston did. “[I]f your policy goal is to lump in religious speech with fighting words and obscenity, if it is to celebrate only a ‘particular’ type of diversity consistent with popular ideology, the First Amendment is not exactly your friend.”

The opinion of the Court can be read in full here.